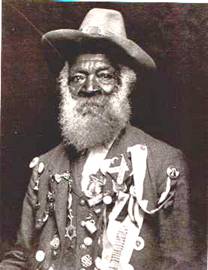

Photos: Charles Hicks, Black Confederate, Company F, 14th Georgia Infantry Regiment. Charles Hicks was sent home to help protect family and home from

The Causes Of The War

Were Blacks “Forced to Fight” for the Confederacy?

Some historians, and students of history, will grudgingly admit that some blacks did fight for the South, but will add that they were “forced” to fight. The implication is that their service is diminished, or dismissed, if they were “forced” to fight.

Were blacks forced to fight for the Confederacy? Let us look at six sets of facts:

1. Many Blacks Were Free Men of Color

Not all blacks were slaves— the number that were Free Men of Color is given as low as 186,000 (C. H. Wesley) and as high as 500,000 (Dr. Edward Smith). These estimates are of 3,880,000 total blacks in the South. When we discuss “forcing” men to fight, we must speak not only of forcing slaves to fight, but also about forcing Free Men to fight. Free white men were also “forced” to fight—the South had the first draft in American history—yet we hear nothing about how whites were “forced” to fight for the South.

There were more Free Men of Color in

the slave states than there were in the

The author of this article knows many

white, brown, and black men who were “forced” to fight in another war--

2. Union Surgeon Steiner Sees Uniformed Confederate Blacks with Weapons

Dr. Lewis Steiner, Union Surgeon,

Chief Inspector of the United States Sanitary Commission, observed General

Stonewall Jackson's occupation of

Over 3,000 Negroes must be included

in this number [of 64,000 Confederate troops]. These were

clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured

If you “force a man to fight,” at what point do you turn over all your weapons to him? Where are other examples of men “forced to fight” who carry the “rifles, sabers, knives, etc.”? Who would turn over their weapons to someone who is serving against their will?

Steiner mentions blacks wearing “coats with Southern buttons.” In 1862, no soldiers wore combat infantry badges or other badges on their uniform— coat or jacket buttons were the nearest thing to a combat uniform decoration. The buttons often identified the branch of service of the soldier—cavalry; infantry; artillery; or the state of service. The distinction between brigadier and major general in the Southern Army was made not on rank insignia, but on button placement (groups of 2 rows versus 3 rows); the distinction between officer and enlisted was made again with buttons—one column versus two columns. A report from a United States observer, commenting on Confederate soldiers, observing 3000 black soldiers wearing Southern coats with Southern buttons, and carrying all kinds of weapons— this does not sound like a description of men who were “forced to fight.”

3. Captured Black Soldiers Escape—and Return South

Strong evidence against the thesis that blacks were “forced to fight” is found in the Tennessee Colored Man’s Pension Applications (TCMPA). Some 285 black Tennesseans filed for these pensions during the 1920s and 1930s. Applicants were not required to describe their combat experience, but many did so anyway. In these descriptions, 17 stated that Union forces captured them. Of those, 6 escaped back to the South (Rollins, 1994, page 81).

The individual accounts are instructive in revealing the motivation of black Southern soldiers:

Dawson Pugh was captured by the Yankees in March, 1863, escaped, and returned to his owner and master, Lt. Frank Pugh (TCMPA No. 192).

Clay Hickerson was captured and when the Yankees tried to take him North, he refused to go and returned to his owner, who told him he was free anyway (TCMP No. 79).

In the spring of 1865, Dave Burns was captured along with “most of my company.” He escaped and returned to his “old master” (TCMP No. 123).

Henry Church returned to the army by himself after leaving his wounded master at home (TCMP No. 19).

George Washington Yancey

was captured with the

How are these

blacks victims? How were they “forced” to fight for the South? Imagine

a soldier who was forced to fight and was captured by the opposing forces--

under what circumstances would that soldier escape from the “liberators” and

make his way back through two lines of armed soldiers, ready to fire at a

moment’s notice? To escape back to the very forces who had

forced him to fight in the first place?

Perhaps to see his wife or children? Yet in all

cases, black Confederates did not return South to see

their family—they returned to their master, or to their army unit.

This does not strike the modern reader as the action of someone who has

been forced to fight—unless those soldiers underwent considerable change of mind

during their service.

Photos: Charles Hicks,

Black Confederate, Company F, 14th Georgia Infantry Regiment.

Charles Hicks was sent home to help protect family and home from

4. UCV Reunions: Were Black Confederate Veterans “Forced” to Attend?

Private Louis Napoleon Nelson, a

black Confederate soldier, served the Confederate States of

Who forced him to attend those 39 reunions? The thesis I am countering in this essay is that blacks were “forced” to fight for the Confederacy—not forced to attend UCV Reunions—but the motivation to attend a veteran’s reunion is not unlike that of serving in the unit in the first place—surely a man forced to serve in a military unit would not go to great expense later to voluntarily attend a reunion of with those same men he was “forced” to serve with?

If Charles Hicks and Louis Napoleon Nelson were the only black Confederates who attended UCV reunions, his case would be interesting but not relevant to the thesis of this essay. But they were not alone. Several more black Confederates are shown in this photo of an Alabama Veterans Reunion about 1928 ….

And three more are shown below in the

cover photo on SCV Historian-in-Chief Charles Kelly Barrow’s book.

These black Confederates are shown at the Confederate soldier’s reunion

in

Photo on cover of

Segars and Barrow book is from

Shown below is the 1890 Alabama Confederate Veterans Reunion. In this photo there are more than 40 black Southern men present. Were they forced to attend?

Photo:

1890

5. How Did Black Southerners Respond When War Was Declared?

In another essay in this set of essays on Black Confederates I offered many examples of how black Southerners responsed to the declaration of War. The following is typical:

In April of 1861, a company of 60

free blacks marched into

This response, and all the others given in the separate essay, to the declaration of war hardly provides any suggestion that these blacks were “forced to fight” for their country. Indeed one could argue based on this contemporary evidence that black Southerners were as eager as white Southerners to fight the enemy.

6. The Valor of Black Confederates

In a separate essay, I give many examples of the valor of black Confederate soldiers. One such example concerned Confederate Levi Miller’s war service. Here (not included in the separate essay) is his Commanding Officer’s account of an instance that reveals Levi Miller’s motivation:

In his letter of recommendation,

This show of patriotism to the

Confederate States of

Proud UCV Veteran: Photo from Randy Armstrong’s website.

Summary

Accounts from the years 1861 to 1865, or shortly thereafter, in the case of the UCV Reunions, were presented above as independent bodies of archival evidence, from pension record applications, photographs, a variety of newspaper articles, Union observers, and elsewhere. All these indicate that black Southerners responded similarly to white Southerners: They responded with patriotism for their country, eagerness to defend their country, and a willingness to shed their blood to establish their country’s independence.

Why did blacks fight for the South? Blacks fought for the same reason that whites fought for the South: To defend their homes, their families, and their way of life. Perhaps it is time to look beyond the false black versus white dichotomy, and look at both blacks, and whites, as the same group: Southerners sharing a common interest, fighting-- at least in a large part-- for common goals.

References

Barrow,

C. K., & Segars,

J. H., & R.B. Rosenburg, R.B. (Eds.) (2001).

Black

Confederates.

Jordan, Jr., Ervin.

(1995).

Black

Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War

Rollins,

Richard, Ed. (1994).

Black Southerners in Gray: Essays on Afro-Americans in

Confederate Armies.

Rank and File Publications,

Smith,

Edward C. (1996). Black Southern Heritage (video).

Taped presentation delivered at Hollywood Performing Arts Center,

Wesley,

C. H. (1927).

Negro Labor in the

Wesley, C. H. (1937).

The Collapse of

the Confederacy.

Contact the author at vp09@earthlink.net